Coop média de Montréal – May 9, 2013

(en anglais)

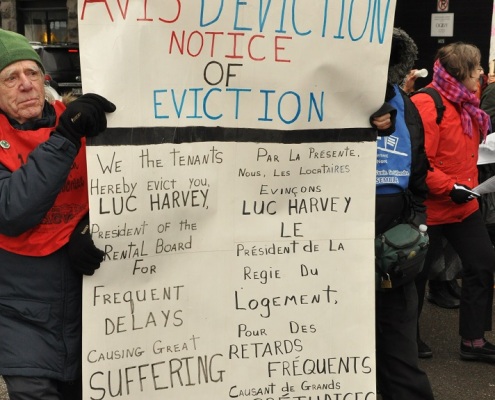

On a wintry afternoon, housing rights activists and community organizers took their time in protesting through downtown Montreal, taking over an hour to walk just a few city blocks. The February 28 “slow march” ended at the offices of the Régie du logement, Quebec’s rental board, which protestors argue has become paralyzed by rising wait times.

On a wintry afternoon, housing rights activists and community organizers took their time in protesting through downtown Montreal, taking over an hour to walk just a few city blocks. The February 28 “slow march” ended at the offices of the Régie du logement, Quebec’s rental board, which protestors argue has become paralyzed by rising wait times.

The Régie’s 2011-12 annual report revealed some grim numbers: the average wait time for hearings for general civil cases—covering everything from rat or mold infestations to repairs to inadequate heat—has reached a record 20.3 months. Wait times vary widely across the province, from three months in Gaspé, to 19 months in Rouyn-Noranda, to a full 25 months in Trois-Rivières, followed closely by the Montreal region at 24 months.

In chilly late February, Montrealers took part in a « slow march » to denounce the increase in wait times for complaints filed with Quebec’s rental board. (PHOTO: Project Genesis.

This is bad news for tenants who are forced to live in often unsafe or unsanitary conditions while waiting for the Régie to set a hearing date. Tenants are left in a state of uncertainty, with no way to check the status of their case. Some end up taking care of the problem at their own expense, or moving out.

This, however, is often not an option for low-income tenants, who lack both resources and options—social housing, for example, is similarly plagued with excruciating wait times.

« People have this need for affordable housing, so they can’t just move out, » says Claire Abraham, a community organizer with Project Genesis, a Montreal non-profit that provides individual services on tenant’s rights in the southwest borrough of Côte-des-Neiges–Notre-Dame-de-Grâce (CDN–NDG). “They’re on a welfare check and can only afford an apartment that’s $500 or less. People often consider putting up with poor housing conditions as part of the deal.”

This has serious implications for the health of tenants, especially young children. In CDN–NDG, one-third of apartments occupied by families with young children have mold.

« Anything related to the health and security of the tenant is considered to be an urgent case, » says Geneviève Trudel, spokesperson for the Régie. « And urgent cases are seen within 1.8 months. » Housing groups disagree, arguing that many cases involving tenants’ health and safety suffer the longest wait times.

“They’re stuck in a legal limbo,” says Fred Burrill, a community organizer with Projet d’organisation populaire, d’information et de regroupement (POPIR), another tenants’ rights organization serving the city’s southwest, in the neigbourhoods of Saint-Henri, Little Burgundy, Cote-Saint-Paul and Ville-Émard. “In the time between when a tenant files a request and when the Régie judge makes a decision, there is nothing for that tenant to do, legally, to fix their problem.”

Cases are examined by recourse, meaning the course of action requested by the claimant. A recourse could be a demand that a landlord restore heat, call an exterminator, repair a leak or reduce a rent increase; or that a tenant pay lapsed rent, repair damage or be evicted. Officially, however, cases are organized into five categories: non-payment of rent, rent fixation and revision, and urgent, priority and general civil cases.

In 1998, the wait time for all civil cases was three months. This leaped to 12.6 months in 2003 and has steadily increased since. The Régie denies there’s a problem, and it has only set a goal of 16 months for general civil case wait times, a number housing activists say is still far too high.

Not everyone is kept waiting so long. The wait time for cases of non-payment of rent—brought exclusively by landlords—has for the last decade remained relatively constant, at just six weeks. The difference in wait times for tenants and landlords has become so large that housing activists are calling it a two-tiered system.

The Régie was set up in 1980 with a mandate of being accessible and impartial, as well as prompt. It was to be an administrative tribunal to which all parties would have equal and fair access. This accessibility and impartiality is now in question. Housing activists argue that although tenants have rights at the Régie, they are effectively denied the ability to exercise these rights. It is, as Burrill says, an “illusion of rights.”

Protesters deliver an « eviction notice » to Quebec’s rental board to highlight the drastic rise in waiting times for tenants’ complaints filed with the organization. (PHOTO: Project Genesis)

Still, the Régie denies prioritizing cases brought by landlords. “Tenants and landlords are treated equally,” says Trudel. “We treat each and every case based on the type of recourse that is asked for, so they’re really treated on a case-by-case basis.”

The evidence suggests otherwise. Non-payment cases brought by landlords account for 90 per cent of the increase in cases brought to the Régie since 1998, and yet wait times for this category have not increased. Civil cases brought by tenants, on the other hand, have only increased by eight per cent, yet they have seen the greatest increase in wait times.

“Regardless of how they spin it,” says Burrill, “in terms of the way they process cases, the Régie essentially functions as a kind of clearing house for evictions. ”

The Régie’s impartiality has also been called into question by recent actions of Régie president Luc Harvey, who was found to have fudged the numbers in 2011 to artificially lower the official wait times of general civil cases.

Project Genesis and POPIR are heading up protests in Montreal as part of a larger provincial campaign to restore the Régie system—and thus restore tenant rights. “We’ve been organizing creative actions, keeping steady pressure on the Régie,” says Abraham.

The recent “slow march” follows an autumn protest that offered “creative » ways of staying warm through the winter without adequate heating. “People were running on the spot, or wrapped in tinfoil,” says Abraham. Though organized with a sense of humour, the issue is serious. Housing groups routinely see families who spend an entire winter, sometimes two, without proper heating.

Media feedback around the campaign has been positive, though it has yet to translate into concrete structural change at the Régie, says Abraham. Severe criticism by the Quebec Ombudswoman has also had little effect.

“We need them to change their way of prioritizing cases at the Régie, fundamentally,” says Abraham. “Organizing cases by the recourse asked for is a serious problem, because it means that simple cases that won’t take very long in the hearing are heard quickly. But that has nothing to do with the actual severity of the problem that the tenant is living in.”

Housing groups want cases dealt with on a first-come, first-served basis; cases dealing with urgent matters of health and safety to be heard within 72 hours; and all cases to be heard within three months. They are also asking the Quebec government to fund the Régie with adequate resources to do this, primarily through hiring more judges.

“It’s the same problem that exists in all social services in Quebec, which is essentially that the social problems caused by a context of austerity can’t be solved under a government model of cutbacks,” says Burrill. “The Régie is completely overextended. It’s operating under a context of shortage.”

Although the Régie itself has not faced cutbacks, housing rights activists argue that its budget remains insufficient to deal with the current housing situation.

“The government’s laissez-faire approach to housing, refusing to fund programs while approving condo developments left and right, has created a housing crisis, which in turn increases the pressure on the Régie,” says Burrill.

The Régie hired eight more judges at the end of 2012, for a total of 42, though they have yet to make a difference. “It takes several months before they are fully operational,” says Trudel. “It will take close to another fiscal year before they are fully accustomed to their task.” Will eight judges be enough to tackle both the backlog and the wait times? “Hopefully, yes.”

Again, the numbers suggest otherwise. Sylvain Gaudreault, minister responsible for the Régie, recently suggested that each experienced Régie judge can make 1,200 judgments a year, meaning 42 judges could deal with 50,400 cases. Last year, however, the Régie received around 78,400 cases. The amount would leave 28,000 cases unheard (a further 23 judges’ worth), nearly doubling the already 30,000-case backlog.

“Eight new judges is a good start,” says Burrill, “but the problem is a deep one. The housing market and the situation for tenants is in total crisis, and it requires a comprehensive overhaul of the way the hiring practices are done and the amount of money that’s put into it.”

Correy Baldwin is a writer and editor living in Montreal. He is an Editor-at-Large at the Media Co-op.